“Is that the only jacket you’ve got?” Gus Grissom’s youngest brother inquired as we set off for the launch pad where the astronaut and his crew were killed 50 years to the day. It was the kind of concern for others you’d expect to hear from Lowell Grissom. “It’s going to be cold out there on the pad tonight.”

I hustled up to my room at a Cocoa Beach hotel to retrieve a sweater, then told Lowell if I brought it I wouldn’t need it. That’s exactly what happened on the eerily still evening a half-century after the Apollo 1 astronauts died on Pad 34 during a countdown simulation that was considered “routine.”

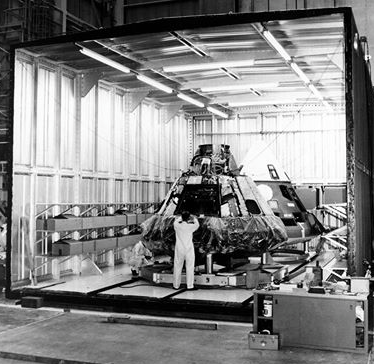

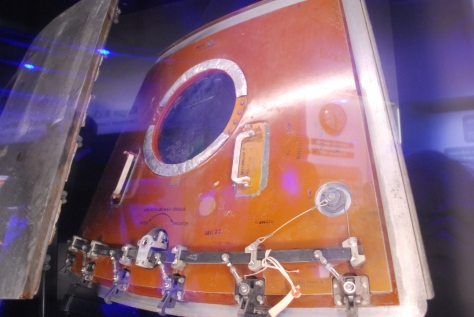

Lowell had invited me to be his guest during two days of observances of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 1 fire. After years of anguish over what to do with brother Gus’s ship, he and others had succeeded in brokering a deal whereby NASA and the Kennedy Space Center at long last agreed to display pieces of the charred spacecraft: the three hatches that contributed to the crews’ sudden and shocking deaths.

The display of those damned hatches in an exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center provided a measure of closure to the astronauts’ families, who were accurately described as the real “heroes” of the Space Race.

On our way out to Pad 34 that Friday evening—the Apollo 1 fire had also occurred on a Friday—I asked Lowell when was the last time he saw his peripatetic brother, the commander of Apollo 1 and the first human to fly twice in space.

“I don’t think anyone has ever asked me that question before,” Lowell responded. It had been several years, he reckoned. Gus was always on the move—from Cape Canaveral to Houston to Downey, Calif., where the faulty Block 1 Apollo command module was being slapped together. In the mid-1960s, Lowell too was pursuing a successful managerial career at McDonnell Aircraft and other aerospace companies.

The brothers’ paths seldom crossed. There was a hint of regret in Lowell’s voice as he struggled to remember. A year, maybe two…. Perhaps a brief phone conversation with Gus in the months before his death….

Gus’s family was well aware of his profound misgivings about the first manned Apollo ship. As always, they figured he’d find a way to fix it, command the maiden voyage of a new spacecraft (as he had on Gemini 3 in March 1965). Then Gus would be in line for a moon landing mission, perhaps the first human to walk on its surface.

That was not to be, and Lowell vividly recalled that Friday evening in January 1967 when the call came from his parents back in Mitchell, Indiana: Gus and his crew were dead, killed by a fire in a deathtrap of a spacecraft during a “plugs out “test. Dennis and Cecile Grissom wanted to let Gus’s siblings know before the reporters knocked on their doors.

Lowell and I made our way to Cape Canaveral Air Force Station to board busses that would take us out to Pad 34. Two were not enough to accommodate the crowd that evening. We joined a motorcade on “ICBM Row” out to the launch pad. On the way, as we passed Hanger S where Gus and the other Mercury astronauts lived and nursed along their spacecraft in the early 1960s, Lowell asked: “How fast do you think Gus drove his Corvette on these straightaways?” As close to the 180-mph maximum of his Vette as possible, we agreed.

The older brother loved fast machines; he had to master them.

A large crowd had gathered already at the crumbling launch pad as the sun began to set and the first stars appeared—Venus was up that still night, and the sweater indeed was not needed. Gus’s wife, Betty—absent from the other Apollo 1 observances—had arrived and was wheeled front row center by son Mark. (She has never missed the ceremony.) Scott Grissom was a nearby, as was Gus Grissom’s great-granddaughter, surprisingly well behaved given the solemn ceremony to follow. You could see in the child’s eyes her great-grandfather’s twinkle.

The ceremony began marking the 50th year since the awful fire. The crew was praised for their sacrifice. Bagpipes played, followed by “Taps”. The flash of cameras recorded the scene. Lowell sat quietly, taking it all in as he had on successive anniversaries. Robert Cabana, the director of the Kennedy Space Center, recalled the words of the astronaut Michael Collins: “We reached the moon because of Apollo 1, no in spite of Apollo 1.”

Those words needed to be said.

A moment of silence at 6:31:04 p.m. eastern time, the exact moment of the first spacecraft call of “Fire!” Then the crowd began to disperse. Astronaut colleagues of Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee lingered to reminisce with Cabana. Just then, the International Space Station appeared overhead. Some of us complimented Cabana on NASA’s exquisite timing. He marveled at the coincidence that the space station should fly directly over Pad 34 as the Apollo 1 observances closed.

The former shuttle commander reminded us that he had hauled up the first two components of the space station. He wasn’t boasting, for Cabana understood he stood on the shoulders of giants like Grissom, White and Chaffee.

Lowell and I retired to the Radisson Cocoa Beach where the families were encamped to drink a toast to the Apollo 1 crew. Masato Maruyama, who again made the pilgrimage from Japan to Cape Canaveral, brought a large bottle of sake, and we all drink a toast to the crew.

As Gus said, “If I die, throw a party!” We honored his wish in the Radisson bar.

Lowell was tired. It had been a long week for him and the other families. They have never adjusted to all the attention. Lowell and I parted in the hotel elevator. It occurred to me as I stepped out and the door closed that Gus Grissom couldn’t have asked for a better brother.

—

(Photo caption: Lowell Grissom and Carly Sparks, Gus Grissom’s granddaughter, with Bonnie White Baer and Cheryl Chaffee during the 50th Anniversary Remembrance of the Apollo 1 fire at the Kennedy Space Center.)