Before there was Breaking News, hourly “bombshell” revelations and clickbait, there was Vincent Kiernan’s radioactive subject, the New York Times science writer and propagandist William “Atomic Bill” Laurence.

Kiernan chronicles the rise of Laurence as a gumshoe reporter beginning in the 1930s to his vaunted status as an atomic “oracle” among colleagues after a decade of documenting development, testing and the dropping of the atomic bomb. Comfortable with his insider status, Laurence soon resorted to “atomic plagiarism” while covering American tests in the South Pacific, copying Pentagon news releases fobbed off as reporting. Other reporters took note—and umbrage.

In the end, the author judges that Laurence the atomic cheerleader was a mere “science writer,” not a science journalist. That trend continues to the present.

You could make the case that reporters like Laurence contributed to the defeat of fascism by reporting and analyzing facts. Instead, as Kiernan shows, Laurence used his pre-World War II dabbling as a playwright and dramatist to juice his wartime reporting on otherwise dry science topics. Laurence’s ostensible goal was educating readers about the miracles of technology, but too often he succumbed to what the author calls the “razzle-dazzle of science.” The dean of the science writers quickly determined from his lofty perch that there was profit and access to power in embellishing the mysteries of physics and other scientific pursuits.

If truth be the first casualty in a war, then journalists-for-hire like Laurence were the foot soldiers who abdicated their responsibility as truth-tellers to power.

The key was more Eureka! moments and fewer mathematical formulas.

Kiernan, a former colleague, has previously chronicled the rise of embargoed journalism, a pernicious news management tactic used by science journals to maximize publicity. The practice has transformed peer-reviewed science into a hype machine designed to give incremental advances the patina of yet another a scientific breakthrough. As journalism professors instruct, untroubled by deadlines and the need to generate “traffic,” Resist Break-Through-itis!

Kiernan demonstrates that Laurence was the original practitioner. What’s more, “Laurence kept secrets,” the author notes, thereby endearing himself to his government handlers while becoming a political operative.

Science writing is mostly about using analogy and straightforward prose to help readers understand increasingly complex subjects. You can’t fake it; there are innumerable traps and ways to get the story wrong. And those Eureka! moments remain few and far between. Most scientific and technological advances result from years, often decades, of painstaking work conducted by researchers laboring in obscurity.

But today’s page-view obsessed media, gaming the Google algorithm to move up the search engine rankings, more often than not overplay scientific advances, embracing “break-through-itis.” It was Laurence and his front-page stories in the Times and elsewhere about early fission research at Columbia University that laid the groundwork. The trumpeting of scientific research and the marketing of dubious technological advances has become the journalistic norm.

Kiernan delivers an unsparing account of Atomic Bill’s machinations, and the Times’enablement, documenting Laurence’s career as a shameless promoter of atomic power while downplaying the horrific effects of radiation on A-bomb victims. In so doing, he shed any pretense of journalistic integrity or search for the truth.

In describing Laurence’s willingness to lay the foundation for decades of misinformation about the dangers of nuclear radiation, Kiernan acknowledges contemporaneous concerns about a bloody stalemate with Japan that drove A-bomb decision. Nevertheless, the author found “no suggestion that Laurence had any qualms about providing a false cover story for the government.”

As the U.S. military sought to downplay radiation dangers after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Laurence also went along with news management schemes choreographed by the head of the Manhattan Project, Lt. Gen. Leslie R. Groves. This was the price Laurence was more than willing to pay for exclusive access to the government’s atomic secrets.

Atomic Bill describes how Laurence was an eager participant in Groves’ plan to control the A-bomb narrative. Along with timing the release of President Harry Truman’s announcement of the Hiroshima attack to maximize coverage in morning and afternoon newspapers, Groves unleashed a torrent of previously classified material. Again, Laurence played ball in exchange for access.

Kiernan’s account also illuminates the journalistic reality of America’s largest and most influential media outlets: On matters of national security, including momentous events like development of the A-bomb and the military decision to use it twice against Japanese civilians, the so-called liberal media nearly always falls in line to support government policies. The latest example being the largely unvetted New York Times coverage of alleged Iraqi nuclear weapons.

The author also demonstrates that the politicization of science and the embrace of alternate “facts” in many ways has its origins in the hucksterism of writers like William Laurence.

Those methods also refined the Yellow Journalism tactics employed during the rise of the American Empire at the beginning of the last century as well as slavish media support for the Vietnam War until well after it was too late. If truth be the first casualty in a war, then journalists-for-hire like Laurence were the foot soldiers who abdicated their responsibility as truth-tellers to power.

By the 1960s, riding his reputation as an eyewitness to U.S. atomic tests and the obliteration of Nagasaki, Laurence had hooked up with New York City urban planner and infamous “power broker” Robert Moses. The profitable publicity partnership designed to promote and bankroll the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair ultimately proved a career killer, and Laurence was forced to resign from the Times.

Atomic Bill and his wife Florence spent their last years isolated in Mallorca, largely abandoned by their powerful benefactors. After years in the limelight, Laurence was reduced to what he was: a small, petty man selling his services to the highest bidder.

The author is no match for his subject as a dramatist. That’s all to the good. As a veteran science journalist, educator and critic, Vincent Kiernan does what any author should strive for: telling an important story in a compelling way.

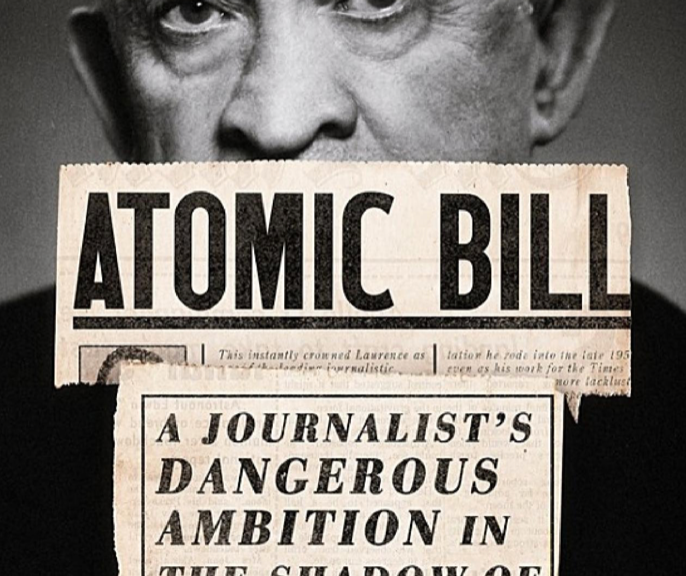

Atomic Bill: A Journalist’s Dangerous Ambition in the Shadow of the Bomb, by Vincent Kiernan, Cornell University Press, (Publication date: Nov.15, 2022).

–George Leopold is executive editor of The Ojo-Yoshida Report and author of Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom.